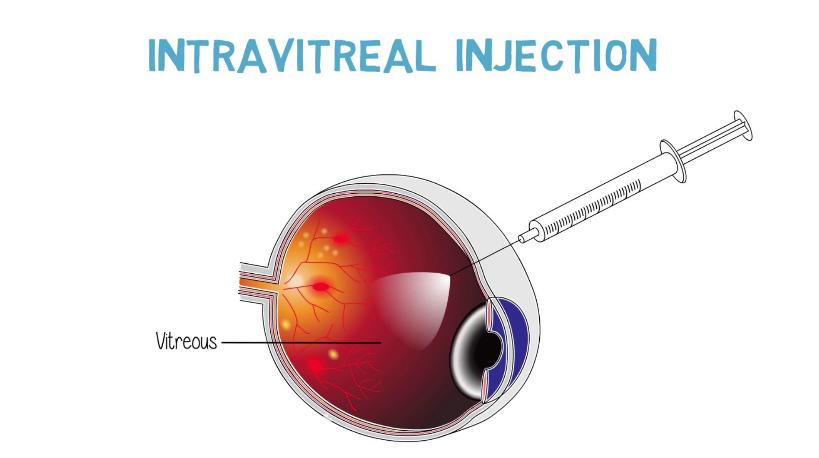

An intravitreal injection is an injection of a drug directly into the cavity of the eye, namely, into the vitreous body, which occupies a large part of the eye. An intravitreal injection provides highly effective, targeted delivery of the drug to the posterior chamber of the eye, thereby creating an optimal concentration of the drug over a long period (2-9 weeks). The structural features of the eye do not allow drugs injected intravenously or intramuscularly to be delivered to the retina. Therefore, the only way to achieve this is intravitreal injection.

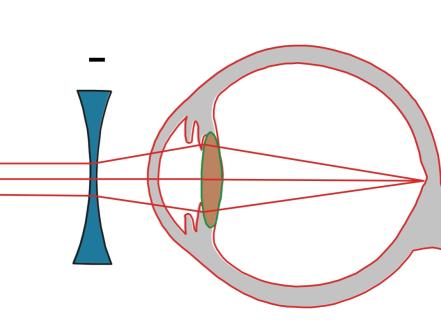

Diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes mellitus associated with the development of new, abnormal blood vessels in the retina or chambers of the eye, which can lead to bleeding and macular edema. To prevent and stop the overgrowth of abnormal blood vessels, anti-VEGF drugs are injected into the eye cavity. VEGF is an endothelial vascular growth factor, which stimulates the development of abnormal vessels. The main anti-VEGF drugs are aflibercept (Eylea®), bevacizumab (Avastin®), and ranibizumab (Lucentis®).

Benefits of intravitreal injections

With the intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF drugs, the removal of macular edema improves vision in about half of patients, and further vision loss is stopped in more than 90% of cases. These results depend on the size and duration of the pathology. Repeat injections are usually necessary to consolidate the successful result.

Preparation for the injection

- Use the antibiotic drops or tablets prescribed by your doctor within 3 days before the injection;

- Eat as usual;

- On the day of the injection, feel free to take your regular medications;

- Tell your doctor if you have any medical problems or allergies to the drugs prescribed.

What are the contraindications for anti-VEGF therapy?

Contraindications for intravitreal injections are:

- oncological diseases of the eye;

- lack of light sensation;

- disorders of the blood coagulation system;

- severe somatic condition;

- acute inflamed eye.

How is an intravitreal injection performed?

Intravitreal injection is an outpatient procedure. It is done in the operating room to minimize the risk of infection. Before the procedure, pupil dilation drops and a local anesthetic are administered. After anesthesia is administered, special eyelid dilators are placed over the eyelids to keep the eye open during the procedure.

The injection is done with a small needle in the white part of the eye. The injection itself takes 3 to 6 minutes. During the procedure, the patient may feel a slight pressure sensation in the eye. After the injection, a short-term increase in intraocular pressure is possible. In patients with glaucoma, the pressure stabilizes more slowly and must be monitored.

What to do after an intravitreal injection?

There are no special restrictions after the injection. It is recommended not to drive for 6 hours after the injection, as the dilating drops can blur your vision.

The antibiotic eye drops should be continued for 3 days. Usually, pain is not observed. It is normal to feel a foreign body in the eye. In this case, one of the artificial tear medications should be additionally instilled.

A small subconjunctival hemorrhage or "eye floaters" may also appear. These effects will disappear over time.

It is recommended that you do not rub, touch your eyes, or swim for several days.

If you have severe pain, increased sensitivity to light, or decreased vision, you should see an ophthalmologist.

The next visit is usually scheduled in 2-4 weeks. Repeated injections may be administered over several years. Their necessity is determined individually, during the clinical examination, by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescence angiography (FAG).

Complication risks of intravitreal injections

Every injection, regardless of the drug injected, carries a 1:1000 risk of complications. The most serious of these are:

- Intraocular infection (endophthalmitis).

- Blockage of the main artery of the eye.

Other rare complications include:

- Retinal detachment;

- Intraocular bleeding (hemorrhage);

- Damage to the lens and the development of cataracts;

- Increased intraocular pressure.

All of these are treatable but may threaten visual impairment